Benin Gender Challenges

This dataset provides comprehensive insights across all regions of Benin, focusing on various gender and child-related issues such as pregnancy assistance and school attendance.

About

Gender inequality in Benin is driven by regional disparities in access to healthcare and education, creating a cascading effect of disadvantage. This dataset, derived from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program, highlights how limited access to professional maternal care in certain regions leads to childbirths that are not attended by skilled healthcare providers.

This lack of professional assistance increases health risks for both mothers and infants, perpetuating cycles of poverty and limiting opportunities for women’s social and economic advancement.Additionally, unequal access to education further exacerbates gender disparities, particularly in primary and secondary school attendance.

In regions with fewer educational resources, girls are more likely to drop out of school early, often due to early marriage or childbearing, which in turn restricts their ability to gain skills and access better economic opportunities. This lack of healthcare and educational access creates a reinforcing cycle, where inadequate services in one area contribute to further inequality in others, entrenching gender disparities across generations.

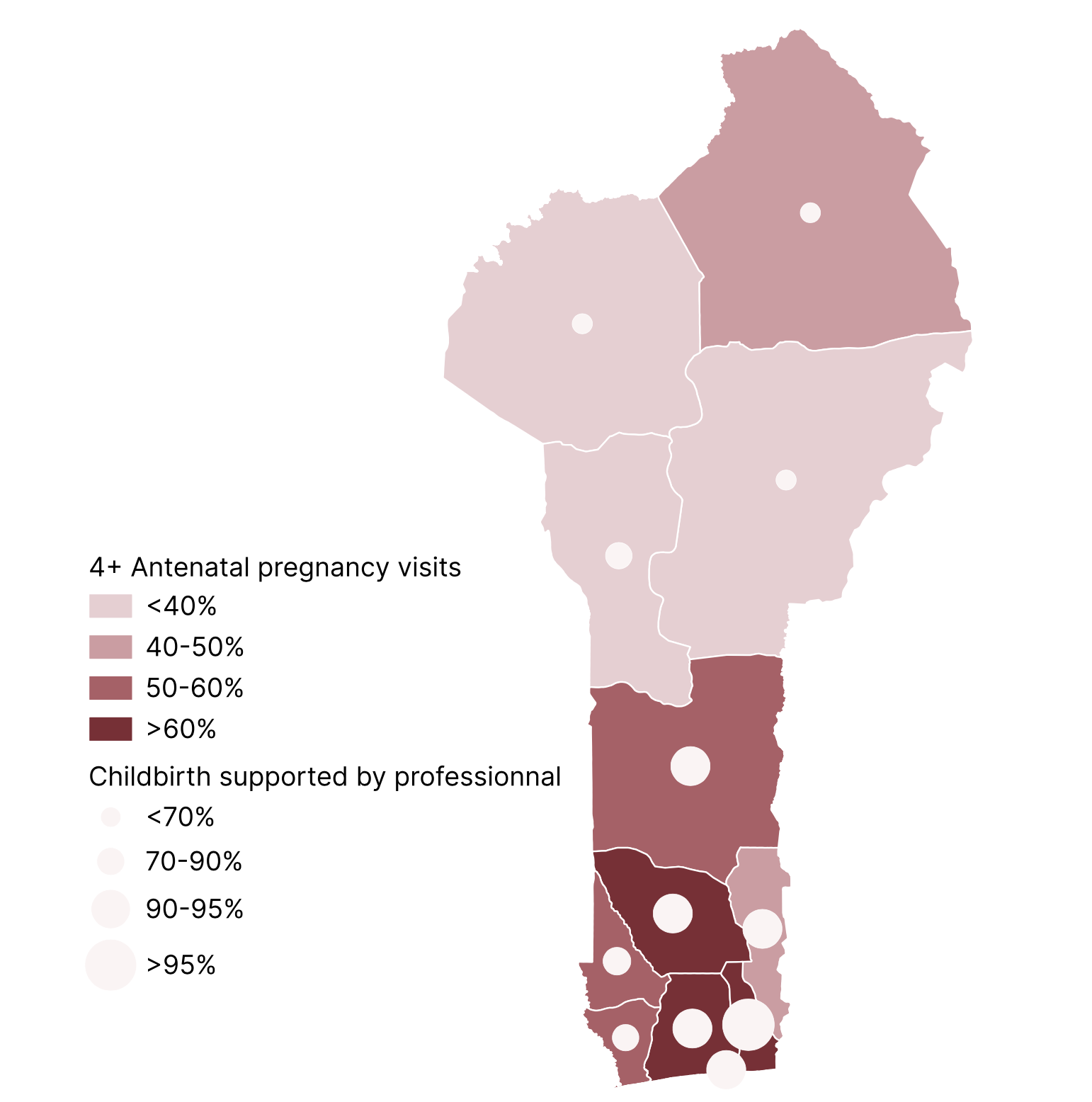

Regional Disparities in Antenatal Care and Childbirth Support in Benin

The map reveals significant regional disparities in antenatal care and professional support during pregnancy. In Atacora region, in the north of Benin, only 25.5% of women attended neonatal visits, with 66.7% receiving professional care during childbirth. In contrast, in Littoral (Cotonou), 81.8% of women had antenatal visits, and 93.8% were accompanied by professionals.

These differences stem from varying healthcare access and infrastructure. Littoral region benefits from better healthcare facilities, more skilled professionals, and greater access to prenatal services, leading to higher rates of professional accompaniment.

In contrast, Atacora region faces challenges such as limited healthcare infrastructure and fewer trained professionals, resulting in lower antenatal care uptake and less professional support. This underscores how regional healthcare disparities directly influence maternal health outcomes.

Gender Parity in Primary and Secondary School Attendance in Benin (2001-2017)

.svg)

The graph reflects the evolving gender dynamics in education across Benin, showcasing improvements in gender parity, particularly at the primary level. From 2001 to 2017, the Gender Parity Index (GPI) for primary school attendance increased from 0.75 to 0.91, indicating substantial progress in narrowing the gender gap.

This trend likely stems from policy interventions aimed at promoting equal access to education for both genders, such as targeted scholarships, infrastructure improvements, and community awareness programs that have prioritized girls' education.

However, the GPI for secondary school attendance presents a more complex picture. While it has improved from 0.62 in 2001 to 0.7 in 2017, the slower pace of change suggests persistent barriers that disproportionately affect girls’ continued education. These barriers include socio-economic factors, such as the opportunity cost of education, early marriages, and limited infrastructure in rural areas.

Furthermore, the GPI for secondary education remains below parity, indicating that while girls may have more access to primary education, retention and progression into secondary school remain significant challenges.

The dataset includes aggregate data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program for Benin, covering five survey periods: 2001, 2006, 2012, and 2017.

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program for Benin

Use Cases

Optimizing Family Planning and Maternal Health Interventions: By analyzing variables like unmet need for family planning, access to antenatal care, and maternal health outcomes, organizations can tailor interventions to address specific regional challenges. These insights help allocate resources to areas with higher maternal and child mortality rates, ultimately improving healthcare access and outcomes for vulnerable populations.

Empowering Women through Health and Economic Workshops: Data on women’s use of contraception and maternal health services can inform programs designed to promote women's economic empowerment. By understanding regional disparities in reproductive health, targeted initiatives- such as microfinance or workshops on family planning and economic decision-making - can be developed to enhance women’s autonomy and economic independence.

Strengthening Early Childhood Nutrition Programs: The dataset’s focus on early childhood indicators, including birth weight, ARI treatment, and breastfeeding practices, can guide the creation of targeted programs focused on the first 1,000 days of a child’s life. Tailored interventions in regions with high rates of stunting or underweight children can positively impact long-term physical and cognitive development.

Limits

Response Bias: Respondents, especially women, may not have felt fully comfortable providing accurate responses, particularly on sensitive issues such as whether they have been victims of violence (e.g., wife beating). Cultural or social pressures could have influenced the honesty of their answers, leading to potential underreporting or bias in the data.

Geographic and Sample Representation: The dataset's representativeness may be limited by the regions surveyed and the sample size in each area. The diversity of geographic zones covered, as well as the number of respondents in each region, could impact the ability to generalize the findings. In regions with fewer respondents or those with distinct local contexts, the data may not fully reflect the experiences of the entire population.

Temporal Limitations: Given that the survey is conducted every five years, the data may not capture more recent changes in social, economic, or cultural trends. Rapid shifts in public attitudes, policy changes, or external events (such as a health crisis or economic downturn) could influence responses, making the data less reflective of the current situation or future developments.